Jitney Craze: 1914-1918

The first historical incidence of ridesharing success was the tremendously popular yet short lived “Jitney Craze” beginning in 1914. In 1908, the Ford Motor Co. began offering the Model T, the first mass-produced automobile that was affordable to the average “successful” person. The vehicle’s popularity soared; in 1908 only 5,896 Model T’s were sold but by 1916 sales had soared to 377,036 nationwide (Hodges, 2006). With the increasing penetration of the relatively affordable automobile, streetcars faced their first real competition in the urban transport market. In the summer of 1914, the US economy fell into recession with the outbreak of WWI and some entrepreneurial vehicle owners in Los Angeles began to pickup streetcar passengers in exchange for a ‘jitney’ (the five cent streetcar fare). The jitney idea spread incredibly rapidly; by December 1914 (merely 6 months after the idea was believed to have been conceived) Los Angeles had issued 1,520 chauffeur licenses for jitney operation (Eckert & Hilton, 1972). In San Francisco, jitneys first appeared in 1914 and were first used to transport workers and attendees to the 1914-1915 Panama-Pacific International Exposition. By 1915, over 1,400 jitneys were operating in San Francisco (Cervero, 1997). With the first jitney’s beginning service in Portland, ME in March 1915, the jitney craze had spread from west to east in nine months (Eckert & Hilton, 1972).

Many of the original jitneys operated on well-known streetcar lines and effectively survived by siphoning off streetcar passengers. From the passenger’s perspective, the jitneys offered service improvements over the streetcar. Jitney’s often operated at speeds 1.5 to 2 times faster than streetcars (Eckert & Hilton, 1972) and could occasionally be convinced to deviate from main routes for drop-offs closer to passenger destinations. For passengers, the ability to choose between two service offerings for the same price was also an attractive service feature. While the reliability of jitney service was sometimes questionable (many only ran during peak periods, few ran during bad weather), passengers had a second option in the form of the streetcar. Travel time savings, route flexibility and transport mode choice were the major value propositions for passengers.

Jitney use was not without tradeoffs. Jitney drivers were known to drive aggressively and accidents were frequent. With passengers standing on the back of vehicles and on the running boards, serious injuries did occur. The transport of female passengers raised concerns in some social circles (Hodges, 2006).

An underlying question that remains a topic of debate is whether jitneys constituted a form of ridesharing or unregulated taxi service. To properly answer this question, the impetus for offering rides should be considered. Given the downturn in the economy, stories of unemployed persons purchasing a vehicle and becoming a jitney operator have been cited in the literature (Eckert & Hilton, 1972, Hodges, 2006). In these cases, jitney service could best be characterized as unregulated taxi service, as drivers were operating the vehicle for the express purpose of providing service to others. In other cases, jitney service seemed to be a method of offsetting the costs of private vehicle ownership for trips that were already going to take place. In a survey in Houston, TX on February 2, 1915, of the 714 active jitneys that day, 442 (62%) made only one or two round-trips, suggesting they might be operating as a jitney during their commute to and from work (Hodges, 2006). In these cases, the primary purpose of the trip was likely commuting; providing service to others was secondary. Any additional revenue generated simply offset the cost of vehicle ownership. In these cases, the generation of revenue was not the main purpose for operating the vehicle, so it could be argued that the service was a form of ridesharing.

The downfall of the jitneys was nearly as rapid as their rise. By early 1915, concerns over safety and liability were being reported in the popular press (New York Times, 1915). Streetcar interests and local governments were eager to stop jitney operations to limit losses in revenue. Streetcar operators were losing paying customers to jitneys, and local governments often taxed streetcar operators a percentage of revenue that they earned, so they were losing tax income as well (Eckert & Hilton, 1972). Many local governments implemented license requirements for jitneys, but the regulation with the largest impact was the imposition of liability bonds. Before operating, jitney drivers were forced to post $1,000 to $10,000 in liability insurance. The licensing and liability regulations added annual costs of approximately $150 to $300, or 25-50% of annual earnings for full-time jitney operators. By July 1915, twenty-seven localities had implemented liability regulations (Eckert & Hilton, 1972). It was estimated that of the 62,000 jitneys in operation in 1915, only 39,000 were still in operation by January 1916 and fewer than 6,000 by October 1918 (Eckert & Hilton, 1972).

There are several important reflections to be drawn from the “Jitney Craze” period. First, the original impetus for picking up passengers appears to have been due to the downturn in the economy. For those that already owned a vehicle, the offering of a ride was presumably to offset operating and ownership costs. For those that began offering jitney services during the period, many had been unemployed and saw operating a jitney as an employment opportunity. In either case, personal finance issues appear to have been a factor. Second, liability and safety were two of the major concerns with jitney service. These same issues remain major concerns with ridesharing today. Third, jitney service provision did not appear to be driven in any major way by resource constraints or environmental benefits, it was largely due to gaps in service quality and economic factors.

World War II: 1941-1945

The second major period of rideshare participation, and the period most likely to be identified as the first instance of traditional carpooling, was during World War II (WWII). In a reversal from the jitney era, government encouraged ridesharing heavily during WWII as a method of conserving resources for the war effort. This period of rideshare promotion was exceptionally unique in that it entailed an extensive and cooperative effort between the federal government and American oil companies.

European involvement in WWII began in 1939 but US involvement did not get underway until late-1941 and early-1942. Nevertheless, the federal government had begun making preparations for war much earlier. In May 1941, President Roosevelt established the Office of the Petroleum Coordinator (OPC) (US PAW, 1946). OPC was created to coordinate and centralize all government activities related to petroleum use. The Office was unique in that it relied heavily on industry committees to make recommendations to government; government initiated very few regulations (US PAW, 1946). This structure was chosen specifically because it encouraged all oil industry participants to cooperate amongst themselves, and it was felt that a more cooperative relationship with industry would lead to a greater overall level of voluntary effort.

By July 1941, one of OPC’s industry committees organized the first known petroleum conservation effort in the US. The campaign was launched on the East Coast with a $250,000 advertisement budget funded entirely by industry asking the motoring public to use 30% less gasoline (US PAW, 1946). Recommended actions included lowering drive speeds, proper care of tires and the sharing of rides. By the industry’s own admission, the effort was not terribly successful. A lack of public appreciation of the need to conserve fuel was cited as the leading challenge to be overcome; “this first drive to emphasize to the American people the necessity of gasoline conservation served one important purpose: it showed industry itself the magnitude of the task, and the growing need for a long-range, sustained program of public education” (US PAW, 1946).

In November 1941, industry created their official council that would interact with the federal government. The Petroleum Industry War Council (PIWC, originally named the Petroleum Industry Council for National Defense), a group that consisted entirely of petroleum industry representatives, was the entity that would ultimately design and fund all petroleum conservation activities during WWII (US PAW, 1946). In an odd twist of irony, PIWC held their first committee meeting on Dec. 8, 1941, one day after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the exact day that President Roosevelt signed the declaration of war against Japan. By February 1942, PIWC had established their Subcommittee on Products Conservation (under the Marketing Committee) and had completed the design of their nationwide conservation program by month’s end (US PAW, 1946). After a year and a half of effort, the Subcommittee was discharged in September 1943 and replaced by the higher-level Products Conservation Committee, suggesting the growing importance of oil conservation. This structure remained until the end of WWII. The Products Conservation committee’s programs had three main goals; (a) to provide the public with facts so that everyone might better understand the need for rationing, (b) to obtain better compliance with rationing programs, and (c) to bring about greater conservation of gasoline through car sharing [carpooling] and other measures (US PAW, 1946).

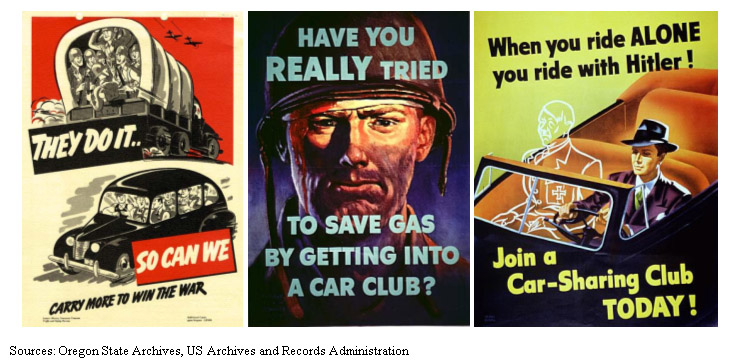

The Products Conservation committee was made up largely of advertising specialists. The bulk of the rideshare initiative (and all conservation initiatives during the War) focused on catchy slogans, posters and newspaper advertisements. While the PIWC spent considerable time developing some of the most recognized posters during WWII, they themselves did not publish them. OPC worked collaboratively with various government agencies including the Office of War Transportation, the Office of Price Administration and the Office of War Administration to distribute the ads that they created (US PAW, 1946). All advertisements were released to the public through a government agency. It is once again worth noting that the petroleum industry volunteered their time and resources to this effort with little financial support from government. At the end of the War, it was estimated that the Products Conservation committees had expended $8M. in private funding to support conservation efforts alone (US PAW, 1946).

While there is plenty of evidence of rideshare promotion during WWII, no information could be found on how successful the initiatives actually were. Some statistics exist on the number of newspaper advertisements placed and the estimated readership reached; however, little appears to be known about the actual level of ridesharing that took place during WWII. As discussed in the introduction to this section, part of the reason may be the lack of a financial transaction when sharing rides. Total auto use and transit ridership can be reasonably measured using financial transaction data, but rideshare participation cannot.

As with the “Jitney Era”, there are some important reflections to be drawn from the rideshare experience during WWII. In contrast to the “Jitney Era”, the main force behind ridesharing during WWII was government-mandated resource constraints (gasoline and rubber) rather than a market response to an economic downturn or a gap in transit service quality. Further, marketers during WWII understood that by appealing to patriotism they could encourage behavior change. There appears to have been a sincere belief that those remaining in the U.S. should make an effort to support their countrymen overseas by reducing their consumption and by making a behavioral change. Third, and perhaps most importantly, was the fact that the promotion of ridesharing during WWII was a large cooperative effort between the U.S. federal government and private industry. It is clear that interests of national importance took precedence over corporate interests during this time period, however, in the absence of a national emergency or compelling long-term threat, it is not likely that this sort of public-private relationship between government and the petroleum industry could be recreated today.

The 1970’s Energy Crises

The third period of interest and participation in ridesharing was during the energy crises of the 1970’s. Interest in ridesharing picked up substantially with the Arab Oil Embargo in the fall of 1973. Throughout the fall and early winter of 1973, President Nixon’s administration realized that action would need to be taken to reduce petroleum consumption. In January 1974, Nixon signed the Emergency Highway Energy Conservation Act, which mandated maximum speed limits of 55 MPH on public highways (Woolley & Peters, [2]). The Act was also the first instance where the US federal government began providing funding for rideshare initiatives. For the first time, states were allowed to spend their highway funds on rideshare demonstration projects (Woolley & Peters, [2]). The 1978 Surface Transportation Assistance Act would eventually make funding for rideshare initiatives permanent (US EPA, 1998).

It was during this initial energy crisis that states began experimenting with High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lanes. The Shirley Memorial Highway in Northern Virginia had opened as a dedicated busway in the center of the highway in 1969 becoming the first highway in the nation to provide dedicated infrastructure for High Occupancy Vehicles (Kozel, 2002). Beginning in December of 1973, vehicles with four or more passengers were also allowed to use the busway. HOV lane construction proceeded slowly through the 1970’s, with interest increasing in the mid-1980’s. While the number of required occupants was eventually decreased to three, the Shirley Highway remains one of the most heavily used HOV corridors in the nation today (Kozel, 2002).

The early 1970’s marked another first for ridesharing; it was the first time that it was recommended as a tool to mitigate air quality problems (Horowitz, 1976). The 1970 Clean Air Act Amendments established the National Ambient Air Quality Standards and gave the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) substantial authority to regulate air quality attainment (US EPA, 2008). After initially rejecting the State of California’s ‘transportation control plan’ to meet Clean Air Act requirements in the Los Angeles basin in mid-1972, the EPA issued its own draft plan in late-1972 (Bland, 1976). The initial plan was met with substantial backlash, particularly a provision that would reduce gasoline consumption during the high-smog summer months by an incredible 86% through an aggressive gasoline rationing system. After public consultations, a much more moderate final control plan was issued in 1973. One of the main provisions of the final plan was a two-phase conversion of 184 miles of freeway and arterial roadway lanes to bus/carpool lanes and the development of a regional computerized carpool matching system (Bland, 1976). Phase One was to be completed by May 1974 and Phase Two by May 1976. By the 1976 Phase Two deadline, not a single lane-mile of roadway had been converted for high occupancy vehicle traffic (the El Monte Busway was opened in 1973 and allowed HOV 3+ in 1976; however, it was designed and operating as a high occupancy vehicle facility prior to EPA’s final control plan and therefore did not count as a conversion) (Bland, 1976). In fact, the next HOV project in LA County would not be constructed until 1985 and by 1993 there was still only 58 miles of HOV lanes countywide (LA MTA, 2009).

The post-1973/74 Oil Embargo period was a time of great interest in ridesharing. With the funding of rideshare demonstration projects in 1974, academic study of ridesharing and of the results of the rideshare demonstration projects began in earnest. The post-73/74 period also saw the creation of the nation’s first metropolitan rideshare agencies (US EPA, 1998). At the outset, these organizations relied largely on marketing campaigns encouraging ridesharing, largely disseminated through roadside signs and public service messages. As research into ridesharing progressed, the importance of employer-based initiatives became better understood and many agencies began to work more closely with large employers (US EPA, 1998).

By the late-1970’s, President Carter proposed multiple initiatives to further encourage ridesharing. In 1979, he appointed the National Task Force on Ridesharing to “expand ridesharing programs through direct encouragement and assistance, and create a continuing dialogue among all parties involved in managing ridesharing programs and/or incentive programs” (Downs, 1980, Woolley & Peters, [1]). His administration also understood the negative effect of parking subsidies on rideshare participation. In 1979, his administration tried to amend the National Energy Conservation Act (NECA) to eliminate subsidized parking for federal employees. The bill faced strong opposition from federal employees and was never passed (S. 930, 1979). In 1980, a bill was even introduced which sought to create a National Office of Ridesharing. As with the NECA amendment, this bill was never passed into law (HR. 6469, 1980).

The energy crises of the 1970’s marked a number of ‘firsts’ for ridesharing. It was the first time that the federal government formally funded rideshare initiatives, it was the first time that ridesharing was prescribed as an air quality mitigation strategy and it was the beginning of formal academic research into rideshare motivations and the potential to reduce petroleum consumption. As with previous periods though, national rideshare statistics were just starting to be gathered, making it difficult to determine how influential the energy shortages and government-sponsored programs had been on participation. Much like ridesharing in the WWII-era, the federal government’s involvement was largely a response to a resource shortage, in this case exclusively petroleum.

While many held strong hopes for ridesharing at the beginning of the 1980’s, low oil prices and strong economic growth throughout the decade and into the 1990’s dashed those hopes.